Lesson understood.

Now that the Butcher of Baghdad has been sentenced to hang, what have we learned?

I know it's a hoary question, but it's still a valid one. The European Union, fainting at the mere thought of violence, simply thinks it's wrong to execute anyone for any reason, as does Amnesty International. Opposition from these quarters was to be expected. After all, they tend to oppose the death penalty in more or less every instance, no matter who it is that's to be executed. No lessons learned here.

There have, however, been a few observers keen enough to learn one of the real lessons of Saddam's ignominious date with destiny. A group of Zimbabwean exiles in South Africa have welcomed Saddam's death sentence, and hopes it sends a message to Zimbabwe's dictator Robert Mugabe, as well as deposed dictators Augusto Pinochet of Chile and former Liberian dictator Charles Taylor, saying:

"[we] believe that together with the Pinochet, Taylor, and other recent cases, this case sends an unequivocally clear and resounding message to dictators and perpetrators of serious crimes under international and national laws. [We] hope that this loud message will not escape the ears of tyrants like President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe and all those who serve under him in the commission of torture and other crimes against humanity"While stating that they "deplore the death penalty as a method of punishment", they welcome the trend of dictators facing justice at the hands of their former subjects in a court of law. As you can imagine, this trial has resonated strongly in countries who have recently rid themselves of their dictators, but less surprisingly, it's created quite an impression on another group: dictators still in power.

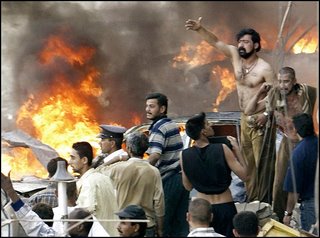

Egyptian strongman Hosni Mubarak is nervously talking about about the "instability" that Saddam's hanging will cause in Iraq, while Venezuelan caudillo Hugo Chavez predictably opposes Saddam's date with the gallows (although he just as predictably supports hanging George W. Bush).

Not surprisingly, most dictators have closed ranks around Saddam because they've drawn exactly the same conclusion as Iraqis and the aforementioned exiles in Zimbabwe have: if they ever have to account for their crimes in a courtroom of their own people, they're as good as dead. No dictator is afraid of the International Criminal Court in The Hague, and frankly, who can blame them? The extradition proceedings take an eternity. They confine you in large, well appointed quarters. And no matter what - under any circumstances - is there any chance of receiving the death penalty.

There isn't a dictator on earth that's afraid of receiving three hot meals a day and cable television for the rest of his life, when the alternative might be answering for genocide, torture and political repression at the end of a rope. Even merely being deposed and killed isn't regarded with quite the same horror. Nicolae Ceauşescu was tried in secret and shot, avoiding the indignity of hanging, and of having his victims testifying before him and making him confront his bloody hands.

Saddam's trial by free Iraqis represented exactly the sort of justice rulers like Saddam worked so hard to avoid, and I imagine that dictators across the world loosened their collars in discomfort when they heard the verdict. This is, quite literally, their worst case scenario - worse even than exile, prison, or being overthrown in a coup d'etat, or even dying in combat. There literally is nothing that scares them more than what Saddam is facing, and it's a fear they should certainly respect.

I don't know if the same day will ever come for Mugabe, Castro, or Omar al-Bashir, but Saddam's fate will give hope to the right people - the people currently being ground under the heel of dictators seeking to restore the justice they've been denied for too long.

No comments:

Post a Comment